Still More Books

For those who might care* I thought I would mention that I've just updated my online "book of books", the database in which I keep a list of the books I've read.† I only seem to get to updating it once a year or so; therefore you'll find that I've added titles from about the past 12 months. Even if you look right away, though, it won't be complete–I just finished another mystery last night.

I was telling Bill (friend of this blog) the other day that I've had a dry spell recently in which the series of books by mystery authors I had been reading ran out and I didn't have leads on new authors to follow-up. What a dilemma! I hate when that happens. My one known resource for some suggestions is the Christchurch [NZ] City Libraries "If You Like…" page of suggestions. It's not perfect but it can help.

Bill and I therefore frequently exchange the names of authors we've enjoyed. So, for you mystery readers, how do you find new authors?

Here's the book of books, before I forget.

Oh, for my benefit and yours, there's a new search function that can find a fragment of text in any of the text fields. If you want to search for "foo" embedded someplace in the midst of such text, surround it with percent signs, the SQL wildcard for "any number of characters" thus: "%foo%". So much easier than trying to remember an author's last name and type it entirely correctly.

———-

* I can't imagine why anyone would, but I don't mind sharing. One reason I keep the database is so that I can find out whether I've read a book before; I keep it online so that I can look at it when I'm at the library.

† I am tempted to say all books except that the list now includes a few thousand titles and it's unlikely that I've remember to write down everything accurately, let alone remembered to write down everything. Besides, there is ambiguity about what, exactly, constitutes a book, and there are times I've included things I didn't include at other times. (What to do with serialized things in The New Yorker, say, or volumes that have "Three Novels by _____"?

To the Moon

I am excited to think that today is the 40th anniversary of Neil Armstrong's and Buzz Aldrin's landing on the moon, while command-module pilot Michael Collins orbited the moon in the Apollo 11 command module. I am, perhaps, less excited that its been forty years since I was 12 years old!

I am excited to think that today is the 40th anniversary of Neil Armstrong's and Buzz Aldrin's landing on the moon, while command-module pilot Michael Collins orbited the moon in the Apollo 11 command module. I am, perhaps, less excited that its been forty years since I was 12 years old!

The photograph is of one of Aldrin's bootprints on the moon (NASA source). At the time Aldrin and Armstrong were walking on the moon, I was watching it on television in the living room of our townhouse in NCO's quarters at Fort Carson, Colorado. The Vietnam War was at its height and so many troops were away from Ft. Carson that my father's battalion of National Guardsmen (he was a Command Sergeant Major) was mobilized and moved for a year from Kansas City, Kansas to Fort Carson to keep the place staffed.

I enjoyed my year living there. Colorado was interesting,* the mountains near the Fort unlike anything we had in eastern Kansas. I was in seventh grade and, shy though I was, I met fun kids and had a good time. I think it was also the first time I fell in love, although I didn't realize it until later. If memory serves, his name was Rob; if memory doesn't serve, that name will serve as well as any other. However, that's really a story for another time.

Being 12 and being in a different and exciting place, and being there when humans reached the moon made everything seem filled with possibilities. From this distance it seemed an almost magical time. Sometimes I wish I could recover the innocence that made it happen; other times, of course, I know better than to wish that and chalk it up to the creeping nostalgia of middle age.

I probably was a child of the Sputnik age, of the American sense of somehow falling "behind" our cold-war rivals. My math and science education was accelerated, such as it was in those days. (Remember, I was precocious and technological because I took a typing course–on an actual upright, manual Remington typewriter–in high school, when learning how to type was treated as a dying art best left to die.) I enjoyed math and physics in college and, for reasons that are still not entirely clear to me, I went to graduate school in physics and became a rocket scientist.

I like space. I like space exploration. We learn more, and more economically, from unmanned missions into the solar system, but human exploration is still the great adventure and, I can believe, growing beyond our planet still the future of the human race. Yes, I read a lot of science fiction in my youth and it was the inspiration of a lifetime, apparently.

We need to keep exploring space. The benefits that accrue to our culture are largely intangible despite all those years of marketers touting Tang and Teflon as worthwhile spin-offs. But intangible does not imply useless. Exploration, discovery, and learning are all a vita part of the growth of human civilization, just as art and music are. Who does not marvel at the glimpses of the edges of the galaxy that we get from the Hubble Space Telescope?

We are returning to the moon. There was a recent lunar orbiter, the Japanese KAGUYA spacecraft, which returned amazing HDTV videos of the lunar surface (and this spectacular earthrise). NASA's lunar reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) recently made it to the moon. Expectations were that it would be able to see remnants of the earlier Apollo missions–and it can. That arrow in the photograph points to the LEM (Lunar Excursion Module) of the Apollo 11 mission. (More pictures of Apollo landing sites.)

We are returning to the moon. There was a recent lunar orbiter, the Japanese KAGUYA spacecraft, which returned amazing HDTV videos of the lunar surface (and this spectacular earthrise). NASA's lunar reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) recently made it to the moon. Expectations were that it would be able to see remnants of the earlier Apollo missions–and it can. That arrow in the photograph points to the LEM (Lunar Excursion Module) of the Apollo 11 mission. (More pictures of Apollo landing sites.)

This anniversary of the first moon landing seems a good time to reflect on what has, and hasn't, happened since then, and to move on into the future. I hope I can help rekindle some of that spirit and enthusiasm for discovery and learning so that we can find a new age of exploration.

———-

* At least in those years before Colorado Springs was infiltrated by Christian supremacists. The last time I was there the city seemed dingy and lackluster and Ft. Carson still had all of its world-war-two era "temporary" buildings.

In: All, Current Events, Reflections

Benedict's Wrist

What an odd juxtaposition of news headlines today.

First, we learn that Oscar Wilde's reputation is being rehabilitated in the pages of L'Osservatore Romano, considered Pope Benedict XVI's mouthpiece. According to the Telegraph [UK], it was a surprise move.

But in an article published on Thursday, L'Osservatore declared that the author of The Importance of Being Earnest was more than "an aesthete and a lover of the ephemeral".

The playwright was, instead, "one of the personalities of the 19th century who most lucidly analysed the modern world in its disturbing as well as its positive aspects", the Vatican newspaper said in a review of a new book about Wilde by an Italian author.

[Nick Squires, "Vatican reconciles with Oscar Wilde", The Telegraph [UK], 16 July 2009.]

Then we hear (for example) that the Pope fell while on vacation and broke his wrist. He now sports a cast.

Are there fears in Vatican City of a limp wrist?

In: All, Current Events, Faaabulosity

My Public Option

Headlines these days seem to be nothing so much as a circus of my pet peeves, whole tag-teams of peeves running up and pushing my buttons as quickly as possible. Let's put aside the amazing kabuki of the senate confirmation hearings of Judge Sotomayor and reflect, once again, on the health-care "debate".

You may recall that I wrote recently ("Corporate Chump-Change Perverts American Policy") about how the vast amounts of money our nation's largest corporations–insignificant to their balance sheets but still larger than the GDP of most countries in the world–spend on "lobbying" (i.e., buying congressional loyalty) corrupts the political process and perverts democracy. One of the facilitating reasons is a ridiculous concept in American jurisprudence that treats corporations as "people" with a Constitutional right to free speech.

There is another facilitator to this farcical aspect of public "debate", of course: the electorate, actual people, human individuals, who seem more than willing to believe anything fed to them by these large corporations (perhaps "spoon-fed" by very, very large spoons).

The long list of absurd, incredible (as in not credible, or "unbelievable") anti-reform talking points developed by the private insurance industry, which are indistinguishable from conservative talking points (guess who writes their speeches) is–well, long and incredible.

Why should people give any credibility to the notions that health-care done right in the US–universal, single-payer coverage–will cause "socialism", will force us to "live like Europeans" (why not "live like Canadians?), will take away choice, will deny service, will be un-American, when 1) these talking points are patently ridiculous and easily discounted if one looks at the facts (must I insist on looking at "true facts"?); and 2) these talking points are developed by the self-serving industry that has enormous resources to spend on defeating any health-care reform that has a role for government insuring the uninsured?

It is not just that the health-insurance companies have a vested interest in the status quo, and a great deal of money to spend trying to keep it that way, but their arguments do not stand up to even the most superficial scrutiny.

Beyond that, we should know their tactics by now; they're the same tactics developed by the tobacco industry and used for the past two decades by most regulated industries: obfuscation, casting doubt, innuendo, and outright lies, whatever it takes to avoid good-faith debate and scuttle any legislation that appears to them to be a regulation. A number of legislators, of course, have been converted to a "free-market", anti-regulatory outlook through "campaign contributions" from the regulated industries or, worse, through ideological reflection. (What excuse there is for economists escapes me.)

It's probably the scientist in me, one used to reading truth in nature, who throws up his hands in frustration and lack of understanding at how some people can keep saying things that are demonstrably not true, and that have usually been demonstrated not to be true.

Here is the point, I suppose, where I would list and then analyze the tactics that health-care insurers are using 1) to increase their profits (more precisely, their "medical-loss ratio") by dumping customers from their rolls who make the mistake of making claims; and 2) to scuttle useful and necessary health-care reform with lots of money and lots of not-truth.

Fortunately, I don't have to. Here's a segment from an episode of Bill Moyers' Journal (10 July 2009) in which he talks to former Cigna PR executive Wendell Potter; they cover it all very clearly in a discussion of about 38 minutes.

It seems clear to me that the only way to shift the attention of the bloc of health-insurance companies, unified by their common enemy of regulation, is to find the competitive wedge that would set them all snapping and biting at each other's throat rather than trying to pervert federal policy.

One possible idea might be this implementation of a public option: public health-care could be provided through, say, a competitive bidding process where a 3-year contract to provide public health-care is let to the lowest bidding health-care insurer. Performance based incentives would be useful in ratcheting up the competition.

To be honest, I think it would be a terrible, expensive, and wasteful approach. On the other hand, talking about it might prove useful in keeping the "debate" over health-care reform a little more honest. Could the benefit of redirecting "lobbying" money and the focus of that money be anything other than salutary?

In: All, Current Events, Feeling Peevish

Intellectual Abuse & "Insidious Creationism"

Creationist advocates of intellectually dishonest ideas like "teach the controversy", or "evolution is only a theory" are not engaged in a scientific debate. Neither are they engaged in a debate about how science works. Indeed, they are not even participating in good-faith (no pun intended) discourse but are pursuing their own subversive agenda, no holds barred.

An overt part of those agenda includes recruiting children to their world view. Planting intellectually deceitful ideas in the heads of young children makes those ideas less prone to revision as the child matures.

This is not really a summary, but more some thoughts that arrived as I was listenting to the 30-minute talk by James Williams (his website), lecturer in education at Sussex University, called "Insidious Creationism". (Given on 8 June 2009 at a day conference called "Darwin, Humanism and Science".) I watched it at "The Dispersal of Darwin", Michael Barton's blog.

Near the beginning, this idea of "intellectual abuse" caught my attention (transcriptions are mine):

This is why I apply the term "intellectual abuse" to "creationism": I feel that when a person in a position of power and authority, who claims expertise in science, deliberately provides a non-scientific explanation for a natural phenomenon, knowing that to be at odds with the accepted scientific explanation, then that person is guilty of intellectual abuse.

Later on this fanciful image of a graduate in a "creation science" degree program generated a hearty laugh from the audience:

"Intelligent design" explains nothing. Science fails to proceed if that is the approach we take. Science succeeds where there are things that we do not know, that we don't understand. And the role of science is to find those explanations for natural phenomena.

I can't actually see Oxford, or Cambridge, in the near future offering degrees in "supernatural sciences". I can't see somebody going for a science Ph.D. saying, "Well, I've done the tests, I've investigated, I've read all the papers, I haven't got a clue what's going on, so therefore my answer is: It was designed. Could I have my doctorate please?"

The biggest laugh, however, was for the fanciful picture of Jesus holding the baby raptor, an example illustration from an "intellectually deceitful" book aimed at children.

It's not all laughs, of course, even if the presentation is light hearted and digestible. Creationism would be merely a fringe group of ignorable wackos if they were not having such a disproportionate affect currently on educational discourse and policy in this country through deliberately dishonest and misleading tactics and strategies. "Insidious" indeed.

In case you'd like to listen, I'll make it easy:

In: All, Current Events, It's Only Rocket Science, Snake Oil--Cheap!

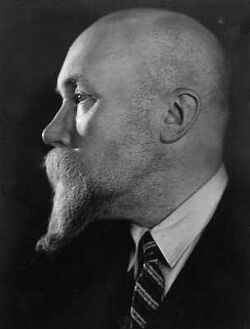

Beard of the Week LXXXIII: Variations on America

This week's beard belongs to American composer Charles E. Ives (1874-1954). He's been a personal favorite ever since I tripped over some of his music a few decades ago.

This week's beard belongs to American composer Charles E. Ives (1874-1954). He's been a personal favorite ever since I tripped over some of his music a few decades ago.

It is hard to find a biography of Ives that does not use the phrases "iconoclastic" and "quintessentially American". (This nice one, also the source of the photo, from the Library of Congress uses "distinctly American"–and "iconoclastic"–just for a bit of variety.) I'm thinking that it could be the iconoclastic bit that attracted me to Ives; I admire the artistic fish that swim upriver.

Ives was born in Danbury, Connecticut. New Englanders take their Americanism very seriously, but without wearing it on their sleeves, and there's lots of Americanism and overtones of rugged individualsim in Ives' music. To describe it in words can make it sound superficial, gimmicky, or even corny, but it is none of those. Ives' music is profound, unique, and uniquely American.

Discussions of his musical heritage always point out two things: that his father, George, was a band leader who was fond of making acoustical experiments, famously of having two bands playing different tunes marching simultaneously down intersecting streets, just to see what it sounded like and to stretch the ears a bit; and that hymn tunes play a big role in Ives' music.

It's true about the hymn tunes–they pop up absolutely everywhere–but to think of his music as somehow "hymn-tune based" trivializes what's going on. His first job, at the age of 14, was that of church organist. It's much more that the musical landscape of Ives' life was populated with hymn tunes and so his musical stream of consciousness often finds them floating by, so he incorporates them into the fabric of his compositions. Here's how the LoC bio (linked above) puts it:

To hear the music of composer Charles Ives is to hear a unique voice in American music, and indeed, in Western music as a whole. His work is at once iconoclastic and closely tied to his musical heritage; in its conception and form, both staggeringly complex and immediately accessible; and in its musical language, both universal and distinctly American.

Ives's work embodies a distillation of the diverse stylistic features of the music of his time, from the traditions of Romanticism prevalent in European art music of the late nineteenth century to the simplicity of traditional American hymn tunes, often juxtaposed in unexpected and even experimental combinations.

It all sounds a bit over the top, but I don't find any of that an exaggeration.

Ives went to Yale and studied music there, but did not become a professional musician. After graduating from Yale in 1898, Ives moved to New York and eventually gained a position in the actuarial department of the Mutual Insurance Company. Curiously, he stopped composing about the time of the first world war. Musically he was largely ignored for decades with his music rarely gaining performance. His first two symphonies were not premiered until the early 50s, half a century after their composition.

I could go on and on about Ives, but this is a holiday, so let's celebrate with a Fourth of July recital!

Variations on "America"

I like the flashy and silly, too, and this is one of my guilty pleasures: Ives' 'Variations on "America" ' for Organ; that's "America", the tune that starts "My country tis of thee…". Ives wrote these variations in 1891, when he was 17. The piece is frequently heard in an arrangement for orchestra made by William Schuman, but I much prefer the piquancy of it performed on organ.

I read an essay about the variations that called them "cheeky". That's probably true, but I don't think they go as far as "mocking". Ives treats the theme seriously enough and does up a clever set of treatments, including a very flashy and noisy toccata for a finale — watch for the pedal fireworks.

When I was in college, our college organist played this once on a recital. He hated the piece so he chose the most outlandish registrations he could think of, and it really bought the piece to life. For the finale he literally pulled out all the stops including the Zimbelstern (a little mechanical, tinkly bell device), which he happily left on and tinkling away when he left the organ bench at the end. Brilliant!

In this performance we haveTom Trenny playing the organ at Trinity Church, New York City. The performance is about 7.5 minutes long. (Note for friends at Facebook: I don't think the YouTube embedded videos survive this translation to Facebook, so you might like to visit the original blog page to enjoy the recital.)

As a bonus treat, here is a video of Virgil Fox playing the variations. I don't care for his performance so much, but he is Virgil Fox, and his introduction to the piece is not to be missed.

General William Booth Enters into Heaven

General William Booth was the founder and first "general" of the Salvation Army. Given what we know about Ives, ponder for a minute on the question of how he might go about a musical depiction of the General at the pearly gates. There's hymn singing, marching, a Salvation Army band, and lots of being "washed in the blood of the lamb". It's an amazing concoction, almost like a 6-minute opera. It appeared in Ives' privately published 114 Songs,* but in this version (apparently by Ives), it's for baritone solo (Donnie Ray Albert), chorus (Dallas Symphony Chorus), and orchestra (Dallas Symphony), all directed by Andrew Davis.

I find it very evocative and very, very Ives.

String Quartet No. 1, 1st Movement, Fugue

The first string quartet is an early piece, composed c. 1900, but not premiered until 1957. (Two sets of notes about the quartet I enjoyed reading: one and the other.)

This is the first movement, a double fugue on two hymn tunes: "Missionary Hymn" (usually with the words "From Greenland's icy mountains….") and "Coronation" (often with words "All hail the power of Jesus' name…"). The former provides the main theme; the latter is heard later as a countersubject. Apparently the fugue (the entire quartet, actually) started life as service music for organ and strings, then was arranged into this quartet.

This particular fugue, which is unusually peaceful, non dissonant, and at first look uncharacteristically Ives, was reused later, orchestrated for a large orchestra, as the third movement of his Fourth Symphony.

Symphony No.4, 1st Movement, Prelude: Maestoso

Ives wrote his Fourth Symphony over a number of years from about 1910 to 1916 (see Wikipedia); it was not performed in its entirely in public until 1965, when Leopold Stowowski did that with the American Symphony Orchestra, which he had founded in 1962.

It is a massive work, scored for a very large orchestra. The second movement, the "comedy", is complex and forbidding and inscrutable and one can't really stop listening to it, either. There are layer upon layer upon layer of sound from which recognizable bits surface every now and then — it always makes me think of recognizable tunes churned up to the surface of a turbulent ocean and then pulled back under again. Perhaps it's Ives reconstruction of his father's "acoustical experiments". This movement is usually performed with two conductors just to keep it all sorted out.

However, it's the first movement that really turned me on originally to the Fourth Symphony. It is a setting with chorus, but no ordinary hymn-tune anthem, of "Watchman, Tell us of the Night"; the colors and mood and rhythmic irregularities are delicious and perplexing. This performance lasts just under 4 minutes.

As a bonus: an analysis / introduction from the Boston Symphony Orchestra's "Classical Companion" about Ives' Fourth Symphony.

Happy Fourth of July!

———-

* I found (here)this lovely quotation from Henry Cowell's Charles Ives and his Music (pp. 80-81):

The 114 Songs forms the most original, imaginative, and powerful body of vocal music that we have from any American, and the songs have provided the readiest path to Ives's musical thinking for most people. Many of them have a touching lyrical quality; some are angry, others satirical. The best of them are musically very daring, with vocal lines that are hard for the conventionally trained artist, accompaniments that are often frightfully difficult, and rhythmic and tonal relations between voice and piano which require real work to master. Even when the melodic line alone presents no special problem, in combination with the accompaniment it offers a real challenge to musicianship. Surmounting the difficulties of this music creates an intensity in the performer that approaches the composer's original exaltation and has brought audiences to their feet with enthusiasm and excitement. But the simplest and least characteristic of the songs are still the most often performed. Like Schoenberg, whose fame rests on musical usages that had not yet appeared in the early pieces ordinarily performed on concert programs, Ives has been represented, as a rule, by pieces that have little or nothing to do with the music that made his reputation.

In: All, Beard of the Week, Music & Art

Things Happen

Sometimes there just doesn't seem to be time–or inclination, perhaps–to write about some of the things that have been going on and, partly, keeping me from writing about what's been going on. Not all of it's bad, either, so don't stop at the first one.

- Some big news I need to mention to some of you at least: a week ago last Monday, on my way to lunch, a reckless and thoughtless driver sideswiped my car and ran me off the road; it seems he had a sudden need to be in my lane despite the fact that I was already there. Since we were going in the same direction, a great deal of kinetic energy was dissipated in noise and buckling metal, but not so much momentum was exchanged. In other words, I was unhurt but my car was fatally injured. I am sad but it had lived a good life and served me well for over 15 years, if you can believe it. Fortunately the insurance picture is slightly smoothed by the frequent admissions of the reckless driver that it was all his fault. We're now in the realm of rental car and shopping for a cheap replacement.

- Earlier this year I wrote an erotic memoir, called "Tom Selleck's Mustache", for a volume (to be called I Like It Like That) edited by Richard Labonté and Lawrence Schimel (Arsenal Pulp Press, expected fall 2009). We went through an odd exchange with copy editors, but I recently did final edits on the "galley" and the book is looking pretty interesting. I'm rather pleased with the way my contribution turned out.

- For the last few years the self-propulsion on my lawnmower had been propelling itself less and less. When the propulsion works, it seems weightless; when it doesn't, the lawnmower is a slug of lead that's no fun to push around our hilly yard. I am absolutely delighted to report that we discovered the easy way to fix the problem (it's a 6.5 hp Toro PersonalPace–let me know if you need instructions) and this past weekend I mowed the lawn in 70 minutes, a task that took 2.5 hours with frequent breaks (for cooling off and complaining) last year.

- Sunday I noticed that the single Rudbeckia maxima we planted a couple of years ago (we bought it as a nearly dead single specimen on sale) has started to bloom. The flower stalks are about six-and-a-half feet tall. I'll have some photos later.

- I already wrote about it but I got the "Eye for Science" project launched last week. I'm pleased about that, but not enough of y'all have stolen the widget yet. What's that about?

- The weather has been nice and we've had some very pleasant parties to go to in the last couple of weeks.

We Plant a Spirea

At the first house I ever lived in, the house from which we moved when I was between second and third grades, there was a large bush that my mother called a "bridal-wreath spirea". I liked that shrub; in my nostalgic memory I adored that shrub, but that may be recovered emotion due to advancing old age. I was buoyed to discover that Isaac, too, had known one in his youth and was longing to have one, too.*

At the first house I ever lived in, the house from which we moved when I was between second and third grades, there was a large bush that my mother called a "bridal-wreath spirea". I liked that shrub; in my nostalgic memory I adored that shrub, but that may be recovered emotion due to advancing old age. I was buoyed to discover that Isaac, too, had known one in his youth and was longing to have one, too.*

Regardless, I now have a firm emotional attachment to the bridal-wreath spirea. Recently I began longing to have one somewhere in our slowly unfolding year-to-garden conversion. The slight drawback is that it is a large shrub and can grow to perhaps eight or twelve feet high and in spread. Still, I had a place in mind.

The interesting question, as I did a bit of online research, was trying to discover what botanical name went with the bridal-wreath spirea that I knew. Online I found at least three distinct plants that, it was claimed, were all the "bridal-wreath spirea".

However, Isaac and I both remembered the flowers of our bridal-wreath spirea quite vivedly and only one plant fit that memory: Spiraea x vanhouttei. That's a picture of it up top. (photo source)

So we asked around and quickly discovered that Elizabeth, one of our more generous gardening friends, said she thought she had a volunteer in her yard and she was certain that it was Spiraea x vanhouttei. She'd be happy to dig it up and bring it over for us to plant in a few days.

That turned out to be the same Saturday morning, about a month ago now, when our new garage doors were being installed. Let's make it a party!

In my mind, when she had said she had a volunteer coming up in her yard from her main plant, I pictured, basically, a tall twig that we would be planting. I hardly expected a vigorous, large young shrub that already had a dozen six-foot long branches. The thing filled most of her Prius that wasn't already filled with Elizabeth.

Planting was successful, and that was right in the middle of our unusual rainy season, so the bush has been kept thoroughly watered and nary a leaf wilted. It now appears to be quite happily settled in, as you can see from this photograph that I took (with a bit of yard for context):

This is the "white" area of the garden. On the left is a Crepe Myrtle 'Natchez', which has very bright white flowers; in front of it is a smallish Philadelphus ("Mock Orange"). In the background, just in front of the fence is the golden deodar cedar we planted a year ago; don't let the image deceive you: it's about 12 feet tall. On the right side behind the fence is a plane tree. The new Spiraea x vanhouttei is in front just right of center. Admittedly the green-on-green color scheme doesn't provide a lot of contrast, but it was spring after all, and everything was green. Nevertheless, you can see that it wasn't a twig! The right blotch in the upper right is a patch of daisies.

I had a couple of links left over from my research, too. I expect I was going to write about this wonderful plant, which the U Arkansas Extension Service called: "Plant of the Week : Vanhoutte Spirea"; they give an excellent historic profile. And, in case the description doesn't bring the blooms to mind, here's a lovely photo of bridal-wreath spirea's flowers. I hope we'll be seeing some of those next spring!

———-

* This is no surprise, really, since we seem to share a brain and are usually found to be thinking the same thoughts at the same time.

In: All, Naming Things, Personal Notebook

Corporate Chump-Change Perverts American Policy

Let's suppose for a minute that your annual income is a modest US$50,000 (modest to some, unimaginable wealth to others).

Don't you hate to see a bunch of that wasted in taxes? Wouldn't you like a nice tax cut, just for you maybe?

Well, let me introduce you to Mr. Congressional Lobbyist. Would you be surprised to learn that, for a mere $50–or 0.1% of your annual income–Mr. Lobbyist will work tirelessly (and legally!) on your behalf and virtually guarantee that the U.S. Congress will pass a bill that will lower, perhaps even eliminate, your taxes?

Is that a deal or what! Only $50! Wouldn't you jump at the chance? (You know, I'm thinking that, at that price, even our Canadian friends might like to join in the fun.)

Last year, 15,000 registered lobbyists spent more than $3.25 billion trying to sway Congress. This year has brought even more of the same. Oil and gas companies spent $44.5 million lobbying Congress and federal agencies in the first quarter of 2009 — more than a third of the $129 million they spent in all of 2008, which in itself was a 73 percent increase from two years before. Medical insurers and drug companies are also digging deep: 20 of the biggest health insurance and drug companies spent nearly a combined $35 million in Q1 — a 41 percent increase from the same quarter last year.

[Arianna Huffington, "Lobbyists on a Roll: Gutting Reform on Banking, Energy, and Health Care", Huffington Post, 25 June 2009; links in original text.]

Recall that last year, in 2008, Exxon-Mobile reported an annual profit (be clear that the number is profit and not gross revenues) of over $45 billion.

They are, of course, only one of the "oil and gas companies" lobbying congress. Nevertheless, the astronomical amount–$45 million in the first quarter of 2009–the oil and gas industry spent lobbying congress is a mere one-thousandth, or 0.1%, of Exxon-Mobile's annual profit alone.

It's akin to asking you for $50 to change the law of the land in your favor. It cost virtually nothing, a blip on the balance sheet not really worth writing down.

This phenomenon is another reason why US Corporations should not be treated as legal persons the way they are now. Corporate money for lobbying should not be treated, as it is now, as constitutionally protected "free speech".

Corporations are not people. Treating large-corporation money as "speech" instead of graft allows it to swamp the real voices of actual American people.

I hope that we are able to keep this in mind during our national "debate" on health-care reform. The "voices" of the big pharmaceutical companies and the big health-insurance companies are very loud right now, making it very difficult to hear the voices of the actual American people.

In: All, Current Events, Snake Oil--Cheap!

"Hiking the Appalachian Trail"

Given the example of wacko Governor Mark Sanford (see, e.g.), a Republican defender of "traditional marriage", I'm thinking that saying one is out "hiking the Appalachian trail" could become a euphemism for "boinking one's mistress at taxpayer's expense while defending 'traditional marriage' ".

Sure, it may not gain the currency of "saddlebacking", which is shorter and sweeter, but it certainly has lots of potential use.

In: All, Snake Oil--Cheap!, Such Language!

Freedom to Choose a Doctor in the US

I find that I'm still thinking today about health-care matters and the train-wreck-in-progress in the US as "we" work towards health-care "reform".

Possibly topping the list of the fear and doubt instilled in the minds of voters by the big health-insurance companies is that universal health-care (usually labeled "socialized medicine") could restrict one's freedom to choose one's own doctor. There's no real reason to think it might happen, but what if the government started telling us what doctor to go to!

But let's think for a moment. Suppose you are in the position of having to find a new doctor as your primary-care physician. You ask around, do some research, and narrow it down to a few names.

What comes next? Aha! Checking your insurer's website to see whether the doctor you've chosen is on the insurer's list of approved providers, i.e., will the insurer accept claims from that doctor for processing.

Wouldn't it be a pity to give up that freedom of choice!

In: All, Current Events, Splenetics

Health Care: "Reform" = "Universal"

I've been reading and listening to talk about health care "reform" recently. As you will realize, for those of us in the US right now that's not a surprise, since it's the one thing all politicians are talking about while they try to figure out how to do nothing about it.

The discussion right now seems to center on nuances (a popular political buzz-word, too) about a "public option"; the nuances are all about how to make sure that the "public option" is neither. Mostly the politicians seem to be trying to hear the whispers of the big insurance companies (the "health professionals" in this scenario) about how to do the "public option" correctly–imagine what "correctly" means in that context.

My own opinion is that we in the US need to implement, and should implement, a universal health-care system and that the so-called "single payer" way to do it is probably the best way to do it. I have friends who tell me that implementing single-payer health care is the worst idea, but the only explanation I've heard for why it's the worst seems to be to say "because it's the worst" very loudly and slowly.

Here's my nuanced position: I do not support the idea of universal health care as a "right"; I merely believe that universal health care is something that a rich, powerful, and compassionate country can and should do. I don't really care, either, whether one wants to call it "socialized medicine"; we know what we're talking about here and I don't care what it's called when it's called names by conservative critics whose tactic is to create fear and confusion about change.

But, all this aside, I have some campaign strategy advice for the politicians who claim to be working on health-care "reform". We know that there will be a great kerfuffle and that when the dust settles that the result will be declared health-care "reform", regardless of whether it actually changes anything about how health care is delivered and paid for in the US. Substitutes that appease the health-insurance industry will be noticed.

In the minds of the average American voter, "reform" on this issue will be judged by how close it comes to creating actual universal health care. Universal health care, free of paperwork and red tape, is an easy concept to comprehend and an obvious target from which to measure how short politicians fall from hitting the target. It's also something that normal people will be able to recognize when they see it.

In: All, Current Events, Plus Ca Change..., Splenetics

They Made Pink Dot

It's a nice day here for a change so I thought something pleasant was in order to counteract all the sourness on LGBT issues that the Obama administration has stirred up lately. I'm behind on the story but I don't think joy goes out of style quickly, do you?

Under the rallying cry "Come Make Pink Dot", pinkdot.org called for people in Singapore to assemble in Hong Lim Park on 16 May 2009 at 4:30pm to form a giant, human pink dot. 2,500 people did.

I love the peacefulness of this demonstration. It made smiles and happiness. It continues to make smiles and happiness via this roughly 4-minute video (YouTube page), which is absolutely charming–and the guy in the pink-feathered hat is pretty faaabulous, too.

An Eye for Science

I have been hanging around this blog for the past week but you might not have noticed. Most of my time has gone into the little box on the left (which you won't see if your reading the RSS feed — so visit the site once, already!), with "Eye for Science" at the top and the little picture in the middle. Go on, click on the picture and see what happens.

For some time, maybe a couple of years, I'd had the idea of putting interesting or provocative thumbnail images on a page that might induce a visitor to click the image, whereupon said visitor gets a big version of the image and a short caption to go with it, a caption high in scienticity. Voilà! A little science moment. Creating those little science moments is Ars Hermeneutica's leading tactic for chipping away at the formidable wall of scientific illiteracy.

This little red box at the left finally implements the idea, not in a final form I'm sure but as a working demonstration of the idea. Oddly, it does it very differently from the way I had originally imagined doing it, even though the end result is identical.

At the foundation is a Flickr group I created last week called — wait for it! — Eye for Science. When I created the group I wanted to seed it with a collection of photographs that suggested the types of images, along with their captions / stories, that I am hoping Flickr members will submit to the group from their own photostreams. Those of you who don't maintain your own Flickr photostream but would like to participate by contributing photographs and stories: get in touch and your image can be put in the group by Euclid vanderKroew (our scienticity mascot, who happens to be a crow); that's what he's there for. Others are now on notice that I'll probably be annoying you sometime in the near future to contribute to the group.

Collecting those images was fun but time consuming. There are a number of sources I used, a mere sampling of the rich resources on the web of public-domain photographs. Many are from US government sources, like NASA and NOAA, agencies with a strong commitment to public outreach and education. Using their images helps our mission and also helps their mission. I love win-win.

Then there was the programming to get the wee box widget to work right. The bulk of that meant sorting out the Flickr API, which works reasonably well but, nevertheless, has gaps in the documentation, not to mention a bug or two. But let's set those frustrating hours aside and focus on the working widget!

If you want to see a stand-alone demo of the widget, here's one. You'll note that there's a link labeled "Steal this Widget!"; clicking it will give you the source code for the little red box, a convenience if you don't want to look at "reveal source" in your browser and try to find it there. Spreading the box around is part of the strategy here, so I'd be delighted for all of you with a place to put it to steal the widget. The randomly chosen content will get more varied and interesting as people contribute images.

One other use that I have almost ready is the "Wall of Science Images" that will live at scienticity.net. The demo is here.

So, my invitation to y'all is two-fold:

- Steal the widget and put it on your site so that more little science moments can start happening; and

- Contribute your own photos with a small science story to the group, either through joining the group and doing it yourself, or with Euclid's assistance.

Have fun looking through the collection!

In: All, It's Only Rocket Science, Personal Notebook, The Art of Conversation

Beard of the Week LXXXII: Space-Time Expands

This week's beard belongs to* author John R. Gribbin (1946– ), a science writer who started life as an astrophysicist. (His website.) I've read and mentioned a few of his books here in the last year or so, and I've been enjoying them so far.

This week's beard belongs to* author John R. Gribbin (1946– ), a science writer who started life as an astrophysicist. (His website.) I've read and mentioned a few of his books here in the last year or so, and I've been enjoying them so far.

The one that I most recently read and enjoyed is John Gribbin with Mary Gribbin, Stardust : Supernovae and Life—The Cosmic Connection (New Haven, Yale University Press, 2000. xviii + 238 pages). Here is my book note.

The book is all about stellar nucleosynthesis: how the elements are made in stars and supernovae. As you may have realized, this is a subject I find fascinating, particularly the history of the discovery of nucleosynthesis. I'm especially keen on the late nineteenth controversy about the age of the sun, a controversy starring two big names in science, Darwin and Lord Kelvin, a controversy that couldn't be settled until the invention of quantum mechanics and the discovery of nuclear fusion.

That problem was finally cracked by Hans Bethe in two papers he published in 1939 in Physical Review ("Energy Production in Stars", first paper online, and second paper online. A very nice short, nontechnical summary of the importance of these papers ("Landmarks: What Makes the Stars Shine?") is also available online. I may have to write more about these sometime.

But the excerpt from Stardust that I wanted to share here has to do with a different question, one that came up in a discussion we had here ("Long Ago & Far Away") following a question Bill asked about the size of the expanding universe.

This doesn't address that question directly, but does answer another related question. I was unclear at the time whether celestial red-shift should be interpreted as the result of actual motion of objects in the universe apart from each other, or as the result of the expansion of space-time itself, or some combination.

The answer is unequivocal in this excerpt: red-shifts are due to expanding space-time. That is, the geometry of space-time itself is stretching out and this is what causes the apparent motion of cosmic objects away from us (with some actual relative motion through space-time going on).

Hard though it may be to picture, what the general theory of relativity tells us is that space and time were born, along with matter, in the precursor to the Big Bang, and that this bubble of spacetime full of matter and energy (the same thing—remember E = mc2) has expanded ever since. The galaxies fill the Universe today, and the matter they contain always did fill the Universe, although obviously the pieces of matter were closer together when the Universe was smaller. Since the cosmological redshift is caused not by galaxies moving through space but by space itself expanding in between the galaxies, it is certainly not a Doppler effect, and it isn't really measuring velocity, but a kind of pseudo-velocity. Partly for historical reasons, partly for convenience, astronomers do, though, continue to refer to the "recession velocities" of distant galaxies, although no competent cosmologist ever describes the cosmological redshift as a Doppler effect. [p. 116]

———-

* The source of the photo is an (undated) article from American Scientist, "Scientists' Nightstand: John Gribbin", by Greg Ross, which has an interview with Gribbin and gives this thumbnail biography:

John R. Gribbin studied astrophysics at the University of Cambridge before beginning a prolific career in science writing. He is the author of dozens of books, including In Search of Schrödinger's Cat (Bantam, 1984), Stardust (Yale University Press, 2000), Ice Age (with Mary Gribbin) (Penguin, 2001) and Science: A History (Allen Lane, 2002).

In: All, Beard of the Week, Books, It's Only Rocket Science

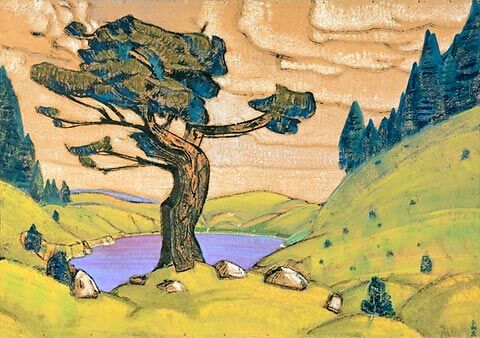

Beard of the Week LXXXI: Pagan Russia

This week's beard belongs to Nicholas Konstantinovich Roerich* (1874–1947), painter, lawyer, peace activist — any number of things, it seems. Excerpting some from biographical notes from the Nicholas Roerich Museum of New York

This week's beard belongs to Nicholas Konstantinovich Roerich* (1874–1947), painter, lawyer, peace activist — any number of things, it seems. Excerpting some from biographical notes from the Nicholas Roerich Museum of New York

Nicholas Konstantinovich Roerich was born in St. Petersburg, Russia, on October 9, 1874, the first-born son of lawyer and notary, Konstantin Roerich and his wife Maria. He was raised in the comfortable environment of an upper middle-class Russian family with its advantages of contact with the writers, artists, and scientists who often came to visit the Roerichs. At an early age he showed a curiosity and talent for a variety of activities. When he was nine, a noted archeologist came to conduct explorations in the region and took young Roerich on his excavations of the local tumuli. The adventure of unveiling the mysteries of forgotten eras with his own hands sparked an interest in archeology that would last his lifetime. […]

In 1895 Roerich met the prominent writer, critic, and historian, Vladimir Stasov. Through him he was introduced to many of the composers and artists of the time — Mussorgsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, Stravinsky, and the basso Fyodor Chaliapin. At concerts at the Court Conservatory he heard the works of Glazunov, Liadov, Arensky, Wagner, Scriabin, and Prokofiev for the first time, and an avid enthusiasm for music was developed. Wagner in particular appealed to him, and later, during his career as a theater designer, he created designs for most of that composer's operas. […]

The late 1890's saw a blossoming in Russian arts, particularly in St. Petersburg, where the avant-garde was forming groups and alliances, led by the young Sergei Diaghilev, who was a year or two ahead of Roerich at law school and was among the first to appreciate his talents as a painter and student of the Russian past.

This is the connection I was looking for this week because I wanted to note that we just passed an anniversary for the premiere of the ballet "The Rite of Spring" (originally "Le Sacre du Printemps"), subtitled "Pictures from Pagan Russia". It's notorious opening-night riot took place on 29 Mary 1913 at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, Paris.

The music, of course, was by Igor Stravinsky; choreography was by Vaslav Nijinsky; performance was by Les Ballets Russes. It was all produced by Serge Diaghilev. The original costumes and set designs were by Nicholas Roerich.

At first reading Roerich seemed to me an unlikely candidate for this activity, but the paragraphs above foreshadow it all: between his abiding interest in archeology and ancient (pagan) Russia, his growth as an artist, and his social connections among the liveliest of the artists working at the time, he was in the right place at the right time with the right ideas and talents, which strongly influenced the shape of the final work. As Wikipedia tells the story of the ballet's genesis:

The painter Nicholas Roerich shared his idea with Stravinsky in 1910, his fleeting vision of a pagan ritual in which a young girl dances herself to death. Stravinsky's earliest conception of The Rite of Spring was in the spring of 1910, in the form of a dream: "… the wise elders are seated in a circle and are observing the dance before death of the girl whom they are offering as a sacrifice to the god of Spring in order to gain his benevolence," said Stravinsky. While composing The Firebird, Stravinsky began forming sketches and ideas for the piece, enlisting the help of Roerich.

The result was not only history, but historic. "The Rite of Spring" endures as a musical masterpiece of the ages, not just the twentieth century, as perhaps the most original and creative piece of musical writing ever. I find it perennially amazing and fresh. Plus, as Bernstein once said, it's "got the best dissonances anyone ever thought up".

And now I'm finding that Roerich is a fascinating person whom I have to investigate further. As one example of his artistic style, here is one of the set designs he did for the Diaghilev production of "Rite", a painting called "Kiss to the Earth (variant 1)", probably implemented as a painted drop.

For a nice collection of paintings by Roerich and his sons, visit the gallery of the Estonian Roerich Society. There are also museums with information and images online: The Nicholas Roerich Museum New York, The Museum by Name of Nicholas Roerich, in Moscow.

Also while I was looking for information, I found this curious article called "Utopia on the Roof of the World" from the magazine Cabinet. The article had something to do with the Shambhala myth and Buddhism, or something, but I read through it and could make much sense of it. However, at the top of the page is a beautiful portrait of Nicholas Roerich by his son Svetoslav Roerich. Apparently Roerich believe Shambhala was located in the Himalayan mountains.

So now I'm interested in knowing why so many people are interested in Nicholas Roerich.

———-

* Photo credit: Nicholas Roerich Museum (of New York), link; original caption: "Nicholas Roerich. June 20, 1929. New York / NRM ref. No 400926"

In: All, Beard of the Week, Music & Art

15 Books

Tim Wilson made me do this at Facebook. I ended up with 16 because his list reminded me of a couple I'd neglected at first. Choose 15 at will.

Don’t take too long to think about it. Fifteen books you’ve read that will always stick with you. First fifteen you can recall in no more than 15 minutes.

- The Tale of the Scale, Solly Angel

- Pride and Prejudice, Jane Austen

- Bright Earth, Philip Ball

- A Clockwork Orange, Anthony Burgess

- Connections, James Burke

- Endless Forms Most Beautiful, Sean B. Carroll

- Mastering the Art of French Cooking, Julia Child, Simone Beck, and Louisette Bertholle

- Darwin's Dangerous Idea, Daniel Dennett

- Stranger in a Strange Land, Robert Heinlein

- Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid, Douglas Hofstadter

- Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, Kinsey, Pomeroy, and Martin

- Conjectures and Refutations, Karl Popper

- The Making of the Atomic Bomb, Richard Rhodes

- Uncle Tungsten, Oliver Sacks

- The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, Muriel Spark

- The Blood Doctor, Barbara Vine (Ruth Rendell)

In: All, Books, Personal Notebook

Sex with Ducks

When it comes to the ridiculous and outlandish "arguments" from the wackos against marriage equality and other equal rights for gay and lesbian people, one can:

- try to ignore them, but then they get out of hand and some people actually believe them;

- try to answer their absurdities while not laughing too much, which some people are very good at, but I tend towards apoplexy or laziness; or

- mock them.

On the whole I think mockery is by far the best response, providing truth through humor on our part in a way that captures the attention and interest of many, yet maximizes irritation of the anti-gay crowd because — I don't think I'm being over harsh, here — they really have no sense of humor whatsoever.

Herewith, then, some video mockery, all thanks to Joe.My.God where I saw them first (here, here, and here).

First up: "Sex With Ducks: the Music Video by Garfunkel and Oates". This is an absolutely charming song having something to do with Pat Robertson's amusing idea that marriage equality is a slippery slope that will lead to sex with ducks (even I couldn't make that up, alas). About 2 minutes long.

Next, a dramatic scene called "The License" (about 4 minutes) in which an excited young couple arrive at a county clerk's office to get their marriage license. Unfortunately, they encounter some unforeseen Levitical difficulties.

In a similar vein to "The License", another dramatic scene (about 4 minutes) called "The Defenders" in which a grass-roots group is celebrating their defense of traditional marriage with, one imagines, a recent referendum. They're ready for new challenges, but first they need to clean up their own ranks a little bit where — you guess it! — there are a few transgressions of ancient Mosaic law as put down in the Bible. Tsk.

In: All, Faaabulosity, Laughing Matters

On Reading Potter's You Are Here

Another book I read and enjoyed recently was by Christopher Potter: You Are Here : A Portable History of the Universe (New York : HarperCollinsPublishers, 2009; 194 pages). Here is my book note.

Potter said he wanted to write the book he wanted to read but no one had ever written. Great idea! His saying that made me think that it was not a book I would have (or could have) written, but that's a good thing. The book is appealing and the ideas presented very thoughtfully, so I think it could certainly reach an audience that other books don't speak to. How to tell? I don't know whether there's any alternative to reading some of it to see whether it works for you.

Anyway, there were, as usual, a couple of left-over excerpts. This first one is a very telling point that doesn't much get discussed.

Einstein's famous theory, the one known as the special theory of relativity, first appeared in 1905 in a paper entitled 'On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies'. It was the German physicist Max Planck (1858—1947) who renamed the theory, though Einstein thought the word relativity was misleading and would have preferred the word invariance instead, a word that has the opposite meaning. [p. 87]

I don't know that I would exactly say it has the "opposite meaning", and even if it does have an opposite meaning, it doesn't refer to the same concept that "relativity" does. However, calling it "invariant" would have been a good, if inscrutable, idea.

"Invariant" means just what it sounds like it means in physics as well as English, something unchanging. But it is used in physics and math to refer to things that don't change specifically when other things are changed, or transformed.

Special relativity provides one of the best examples of something that it physically invariant, too: the speed of light. If all the laws of physics were to "look the same" in various inertial reference frames (see the film "Inertial Reference Frames"), or under transformation to different inertial reference frames, then the speed of light must be the same, or invariant, in all of those frames. The invariance of the speed of light is the central concept of Einstein's 1905 theory "On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies". "Electrodynamics" because that is the "classical" theory of moving charged particles, which, as we saw in the most recent "Beard of the Week", is identical with Maxwell's theory of electromagnetic radiation / light.

This next excerpt I thought was a fair and concise summary of Bishop James Ussher's contribution to the idea stream about the age of the Earth, and as the darling of young-Earth creationists.

In his Annals of the Old Testament, published in 1650, the Archbishop of Armagh, James Ussher (1581—1656), had worked out a chronology of Creation. In a supplement to this work published in 1654 he calculated that Creation had occurred on the evening before Sunday 23 October 4004 BC, a date that does not differ much from the attempts of others, from at least the time of the Venerable Bede (c.672—735), to set a date for Creation. Ussher is today often taken for a fool, but he was a greatly respected scholar of his time, known throughout Europe. According to some biblical scholars, the reign of man was meant to last no more than 6,000 years, taking as evidence a line from the Book of Peter: 'One day is with the Lord as a thousand years, and a thousand years as one day' (2 Peter 3:8). Creation, which began around the year 4000 BC, was set to end 6,000 years later. today, we believe that in 4000 BC the wheel was being discovered in Mesopotamia. Ussher's date was inserted into the margins of editions of the King James Bible from 1701. It is to this version of the bible that fundamentalists have their curious relationship. [p. 212]

In: All, Books, It's Only Rocket Science

Beard of the Week LXXX: Magnets & Relativity

This week's beard* belongs to Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell (1831–1879). He did significant work in several fields (including statistical physics and thermodynamics, in which I used to research) but his fame is associated with his electromagnetic theory. Electromagnetism combined the phenomena of electricity and magnetism into one, unified field theory. Unified field theories are still all the rage. It was a monumental achievement, but there was also a hidden bonus in the equations. We'll get to that.

This week's beard* belongs to Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell (1831–1879). He did significant work in several fields (including statistical physics and thermodynamics, in which I used to research) but his fame is associated with his electromagnetic theory. Electromagnetism combined the phenomena of electricity and magnetism into one, unified field theory. Unified field theories are still all the rage. It was a monumental achievement, but there was also a hidden bonus in the equations. We'll get to that.

He published his equations in the second volume of his A Treatise on Electricity & Magnetism, in 1873. I think we should look at them because they're pretty; I suspect they're even kind of pretty regardless of whether the math symbols convey significant meaning to you. There are four (which you may not see in Bloglines, which doesn't render tables properly for me):

|

; |  |

|

; |  |

I don't want to explain much detail at all because it's not necessary for what we're talking about, but there are a few fun things to point out. The E is the electric field; the B is the magnetic field.

The two equations on the top say that electric fields are caused by electric charges, but magnetic fields don't have "magnetic charges" (aka "magnetic monopoles") as their source. The top right equation gets changed if a magnetic monopole is ever found.

The two equations on the bottom say that electric fields can be caused by magnetic fields that vary in time; likewise, magnetic fields can be caused by electric fields that vary in time. These are the equations that unify electricity and magnetism since, as you can easily see, the behavior of each depends on the other.

There's one more equation to look at. A few simple manipulations with some of the equations above lead to this result:

This equation has the form of a wave equation, so called because propagating waves are solutions to the equation. Maxwell obtained this result and then made a key identification. Just from its form the mathematician can see that the waves that solve this equation travel with a speed given by  , which is related to the product of the physical constants

, which is related to the product of the physical constants  and

and  that appeared in the earlier equations.

that appeared in the earlier equations.

The values of these were known at the time and Maxwell made the thrilling discovery that this speed

was remarkably close to the measured value of the speed of light. He concluded that light was a propagating electromagnetic wave. He was right.

That's fine for the electromagnetism part. What's the relationship with relativity? Let's keep it simple and suggestive. You know from the popular lore that Einstein came up with the ideas of special relativity from thinking about traveling at the speed of light, and that the speed of light (in vacuum) is a "universal speed limit". Only light — electromagnetic waves or photons depending on how your experiment is measuring it/them — travels at the speed of light.†

In fact, Einstein's relativity paper (published as "Zur Elektrodynamik bewegter Körper", in Annalen der Physik. 17:891, 1905) was titled "On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies". (Read an English version here; there are no equations at the start, so read the beginning and be surprised how familiar it sounds.) That's suggestive, don't you think?

Speaking of special relativity, you've no doubt heard of the idea of an "inertial reference frame", a concept that is central to special relativity. But, what exactly is an "inertial reference frame"?

I'm so glad you asked, since that was half the point of this post anyway. You surely realized by this time that Maxwell was partly a pretext. For our entertainment and enlightenment today we have educational films.

First, a quick introduction to the "PSSC Physics" course. From the MIT Archives:

In 1956 a group of university physics professors and high school physics teachers, led by MIT's Jerrold Zacharias and Francis Friedman, formed the Physical Science Study Committee (PSSC) to consider ways of reforming the teaching of introductory courses in physics. Educators had come to realize that textbooks in physics did little to stimulate students' interest in the subject, failed to teach them to think like physicists, and afforded few opportunities for them to approach problems in the way that a physicist should. In 1957, after the Soviet Union successfully orbited Sputnik , fear spread in the United States that American schools lagged dangerously behind in science. As one response to the perceived Soviet threat the U.S. government increased National Science Foundation funding in support of PSSC objectives.

The result was a textbook and a host of supplemental materials, including a series of films. In a discussion I was reading on the Phys-L mailing list recently, the PSSC course was discussed and my attention was drawn to two PSSC films that are available from the Internet Archive: "Frames of Reference" (1960) and "Magnet Laboratory" (1959). (Use these links if the embedded players below don't render properly.) Both are very instructive and highly entertaining. Each lasts about 25 minutes.

Let's look first at the film on magnets; it's quite a hoot. First, the background: when I was turning into a physicist I knew some people who went to work at the "Francis Bitter National Magnet Lab" (as it was known at the time) at MIT. This was the place for high-field magnet work.

Well, this film is filmed there when it was just Francis Bitter's magnet lab, and we're given demonstrations by Bitter himself, along with a colleague, not to mention a tech who runs a huge electrical generation and is called either "Beans" or "Beams"–I couldn't quite make it out. These guys have a lot of fun doing their demonstrations.

At one point in the film we hear the phone ringing. Beans calls out: "EB [?], you're wanted on the telephone." Bitter replies, without losing the momentum on his current demonstration, "Well, tell 'em to call me back later, I'm busy." Evidently multiple takes were not in the plan.

This is great stuff for people who like big machinery and big electricity and big magnets. Watch copper rods smoke while they put an incredible 5,000 amps of current through them. I laughed when Bitter started a demonstration: "All right, Beans, let's have a little juice here. Let's start gently. Let's have about a thousand amps to begin with." Watch as they melt and then almost ignite one of their experiments. It evidently happened often enough, because they have a fire extinguisher handy.

This next film on "Frames of Reference" is a little less dramatic, but the presenters perform some lovely simple but clever and illustrative experiments, demonstrations that would almost certainly be done today with computer animations so it's wonderful to see them done with real physical objects. After they make clear what inertial frames of reference are they take a look at non-inertial frames and really clarify some issues about the fictitious "centrifugal force" that appears in rotating frames.

———-

* The photograph comes from the collection of the James Clerk Maxwell foundation.

† Duh.

In: All, Beard of the Week, It's Only Rocket Science